Turing completeness & Halting Problem

If we say the native Bitcoin scripting language is Turing complete, many people will criticize us.

Turing Completeness refers to a programming language that can implement any computation a Turing machine is capable of. This concept comes from Alan Turing, who proposed the Turing Machine model. It’s an abstract machine that performs calculations by reading and writing symbols on an infinitely long tape.

If a programming language is Turing complete, it means it can simulate all computational functions of a Turing machine. Typically, this requires the language to support conditional branching (like if/else statements) and loops (or recursion) to make decisions based on data and repeatedly perform certain actions until a specific condition is met.

Is it reasonable that a program in an infinite loop could run indefinitely on an infinitely long tape? Is it reasonable to say that a program that can implement an infinite loop is Turing complete?

In fact, simple infinite loops can be implemented with a very basic set of instructions, but if there's insufficient control structure (like conditional branches) and data handling capabilities, such systems cannot be considered Turing complete. Turing completeness requires the ability to express any complex algorithmic logic, including but not limited to loop structures. Furthermore, infinite loops introduce another issue: the Halting Problem.

The Halting Problem, proposed by Alan Turing in the 1930s, is a well-known problem in computation theory. It explores whether there exists an algorithm that can determine whether any given program and its input will eventually stop executing.

Turing proved the Halting Problem is unsolvable. Turing-complete systems can express and execute all possible programs, including those that never halt. The unsolvability of the Halting Problem arises directly from the capabilities of these systems. In short, the robust computational power of Turing-complete systems introduces uncertainty because we cannot predict in advance whether a program will stop in all cases.

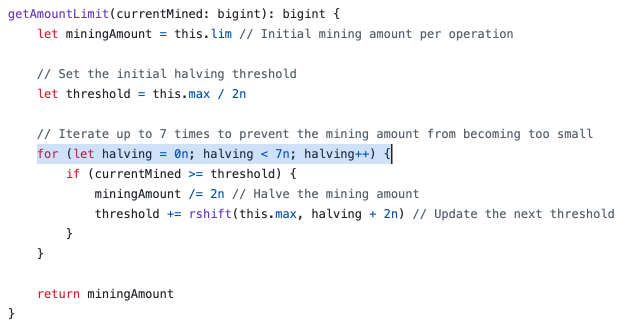

Now let’s see why some claim Bitcoin's script is not Turing complete. Because it lacks loop commands in its opcode, some argue it's not Turing complete. However, assembly language also lacks loop commands, yet no one disputes its Turing completeness. Assembly language provides the necessary tools to implement loops primarily through conditional jump instructions. Bitcoin script is similar to assembly in that loops can be unrolled. For example, to sum from 1 to 100, you could keep adding: 1+2=3, 3+3=6, 6+4=10, and so on until 100. This approach has a benefit—it addresses the Halting Problem. We know that Bitcoin transactions and blocks are limited in size, from 1MB to 4MB, potentially larger. Therefore, an unrolled script will eventually hit this size limit and force the program to stop.

One might say: Bitcoin script language is Turing complete and also solves the Halting Problem.

In Ethereum, the Halting Problem is addressed by charging a fee (gas) for each operation. Theoretically, a wealthy Ethereum user could pay to run a program for a year, potentially clogging the EVM.

However, on Bitcoin , no amount of money can infinitely increase block size, ensuring programs must stop. This is part of the consensus.

In the computing field, there’s an important principle: the KISS principle (Keep It Simple, Stupid). Satoshi Nakamoto adhered to this principle.

Maintaining simplicity in a system is a crucial consideration for designers. In environments like Note Protocol, script size is still controlled, currently providing about 2.5K of script JSON storage space. In the future, it could expand to between 1MB and 4MB.